We get together on a frequent basis, compare notes about what the problems were and what anybody could do to help the situation. And there was a spirit of cooperation pretty much throughout the program. At no point was any team in the dark about what another group was doing, or what support they needed.

—Owen Morris, Chief Engineer of the Lunar Module, Apollo Space Program [1]

Creating High Performing Teams of Teams

This is article two in the SAFe for Government (S4G) series. Click here to view the S4G home page.

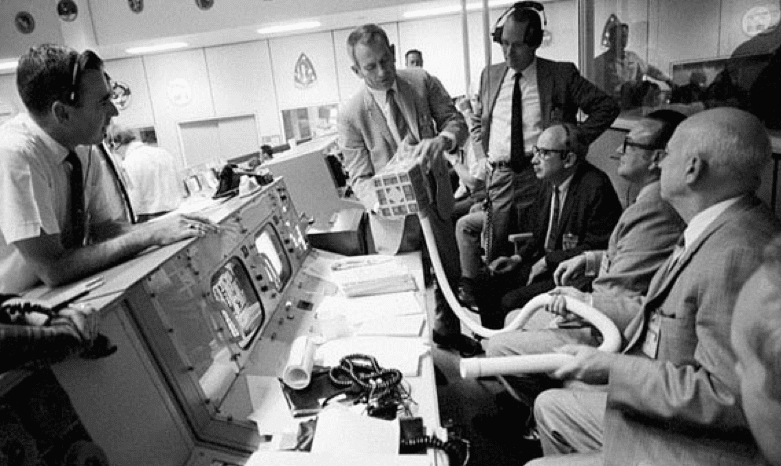

The concept of cross-disciplinary teams of government and contractor personnel working cooperatively to create complex technological systems is not new. Perhaps the most famous illustration of the history of government-industry collaboration is the Apollo space program. That decade-long effort involved over 400,000 engineers, scientists, and technicians from government and from more than 20,000 commercial companies and universities. [1] These teams

- Shared a vision and focus

- Were willing to cooperate with all other teams regardless of their organization

- Solved problems in an open, collaborative fashion

That team-centric environment was put to the ultimate test during the near-tragic Apollo 13 mission.

In more recent years, the use of technology has exploded to become a mission-critical capability for every function in every government agency. Unfortunately, that Apollo spirit has devolved in some instances into an environment of low trust “us vs. them” behaviors between government and contractors. Additionally, in an era of hyper-competition for limited contract awards, multiple suppliers on the same program sometimes work to undermine each other in hopes of unseating the competition in the next re-compete. Finger-pointing and blame game responses to defects and shortcomings frequently overshadow opportunities to collaboratively problem solve for the benefit of the ultimate stakeholder of government systems—the taxpaying citizen.

The first article in this series made the case for establishing a firm foundation in Lean-Agile and SAFe values and principles as the key to faster value delivery in the sustainably shortest lead time. However, these ideals do not function well in low trust environments. If government agencies are going to realize the promise of better mission results through iterative and incremental development, a focus must be applied to building the same type of healthy communication and collaboration among the people creating complex government systems that once achieved the national vision of putting a man on the moon.

Details

Defining High Performing Teams

“The performance challenges that face companies in every industry…demand the kind of responsiveness, speed, online customization, and quality that is beyond the reach of individual performance. Teams bridge this gap.”

— Jon Katzenbach & Douglas K. Smith, The Wisdom of Teams [2]

The Center for Organizational Design describes high performing teams as “a group of people who share common vision, goals, metrics, and who collaborate, challenge and hold each other accountable to achieve outstanding results.” [3] They further elaborate that high performing teams:

- Have a clear and vision of where they are headed and what they want to accomplish

- Are excited about that vision because they took part in creating it

- Act from clearly defined priorities

- Have clear measures of success and receive feedback about how they’re doing

- Maintain open communication and positive relationships with each other

- Identify and solve problems

- Make decisions when and where they occur

- Successfully manage conflict

- Share leadership responsibilities

- Participate in productive meetings

- Have clearly defined roles and work procedures

- Cooperate cross-functionally

Combined with technical best practices for modern systems development, high-performing teams produce mission results that are significantly better than their low-performing counterparts. According to the 2017 State of DevOps Survey [4], high-performing teams:

- Experience code deployments occur 46 times more often

- Lead time from commit to deploy is 440 times faster

- Meantime to recover from downtime is 96 times faster

- Change failure rate is 5 times lower with those changes being 80% less likely to fail

Achieving these results requires creating an environment where high-performing teams can emerge and thrive. Agencies should include language expectations in each industry partner’s contract for how contractors and government personnel will work collaboratively in the best interests of the mission. Contracts should describe how the government expects various contractors working on the same program to cooperate with each other. Also, government leaders create the environment for high-performing teams by how they and their civil service staff interact with contractor team members to create a generative trust-based workforce culture.

Building Healthy Agile Teams

Healthy Agile teams are the primary organizational unit in SAFe. They have many of the attributes of high-performing teams built-in by design. For example, Agile teams in SAFe are small, cross-functional, and self-organizing. They have the trust of the organization to define and execute the work needed to accomplish the objectives of the program. Their Product Owner gives them clear priorities, and they have clear acceptance criteria for each element of functionality they build. They work in single piece flow from a backlog of user and enabler stories that align to a clear and common vision. Each PI Agile teams dedicate time to engage in problem-solving and innovation toward the goal of relentless improvement. They commit to the work they plan every PI and are accountable for predictability over time, measured by consistent delivery of those commitments.

That’s what a healthy Agile team looks like. Anything less falls short of the full potential of Lean-Agile adoption. Successful Agile programs in government have proven that the goal of developing high-performing government and contractor Agile teams is very achievable (Case Studies).

Click here for additional details regarding the composition and responsibilities of Agile teams.

Forming Multi-Organizational Teams-of-Teams

“Today’s rapidly changing world, marked by increased speed and dense interdependencies, means that organizations everywhere are now facing dizzying challenges, from global terrorism to health epidemics to supply chain disruption to game-changing technologies. These issues can be solved only by creating sustained organizational adaptability through the establishment of a team of teams.”

– Gen. Stanley McChrystal (Ret.), Team of Teams: New Rules of Engagement for a Complex World [5]

Few government technology programs can be delivered by a single Agile team. To build complex systems like global GPS networks and veterans eligibility systems, many teams are required. They must maintain all the elements that distinguish Agile teams while working cooperatively for prioritization, integration, and dependency management. They must plan together, work together, integrate together, demo together, innovate together, and improve together. Without a clear strategy to reinforce these collaborative activities, it becomes too easy for vital communications to become siloed and to fall victim to the tyranny of the urgent.

In the context of high speed, variability, and interdependency, the best organizational structure is a “team of teams.” [5] In SAFe, the team of teams is an Agile Release Train or ART. ARTs have many of the same attributes as Agile teams at a fractal-level larger scale. Most government programs are large enough to form one or more ARTs.

Click here for additional details on Agile Release Trains.

Integrating Between Multiple ARTs and Suppliers

Some government technology programs are so large that they involve hundreds or even thousands of practitioners. Examples include Vets.gov, the F-22 fighter jet, and France’s centralized unemployment system. These solutions require far more than a single team-of-teams; they can require many ARTs to build these complex systems-of-systems. It is also common for these large programs to include large numbers of suppliers. Yet all of these practitioners and organizations must work together to build, integrate, test, and deploy a single unified solution.

SAFe provides extensive guidance on how to plan, coordinate and manage programs of this size and complexity. To learn more, read Large Solution SAFe and the Enterprise Solution Delivery articles.

Defining Clear Roles and Responsibilities

Organizing the product development workforce into Agile teams and trains requires roles and responsibilities that are different than traditional top-down organizational chart-based models. For example, healthy Agile teams have moved away from being directed by a team leader responsible for hiring, planning, tasking, prioritization, and performance evaluation. In Agile, the traditional leader model has been turned upside down; the responsibilities are spread among the team and to new roles such as Product Owner and Scrum Master/Team Coach. Team members still report to people managers, who now have more focused responsibilities for hiring, promoting, and facilitating the growth of the practitioners within the teams. Other leaders outside the ART still support the product development process by using their authority to provide the vision, resources, decisions, etc. that allow teams to be successful. A pattern of cooperative collaborations replaces the conventional top-down command-and-control model, with servant leaders using their position and influence to ensure team and ART success.

SAFe provides detailed descriptions of the roles, responsibilities, key activities, and collaborations at every level within the Framework (Essential, Large Solution, and Portfolio). These descriptions can be found in the following articles:

Essential – Agile Teams, Product Owner, Scrum Master/Team Coach, Product Management, System Architect, Release Train Engineer, Business Owners

Large Solution – Solution Management, Solution Architect, Solution Train Engineer

Portfolio – Lean Portfolio Management, Enterprise Architect, Epic Owners

It is important to note that all of these roles describe specific responsibilities to be performed in a virtual SAFe organization, performed by personnel with a wide variety of job titles. Likewise, government agencies should use broad discretion in the labor categories used to fulfill these responsibilities if the roles are performed by contractor staff. This provides maximum flexibility and cost management for both parties while ensuring that practitioners with the right skill sets are performing each of these roles. Significant pre-planning is also recommended regarding which roles are best performed by government personnel versus those that can be filled with government or contract staff.

Finally, many agencies have unionized personnel who will be asked to perform new roles at various levels in a SAFe implementation. The best advice from agency executives who’ve dealt with this issue is to be as proactive as possible, communicating with union representatives about the changes in roles that come with shifting from legacy waterfall practices to SAFe. There are tangible benefits in the form of additional training, certifications, and career growth that make a SAFe transition a win-win for agencies and their union workforce. The key is to create an open dialogue for shared understanding, addressing concerns early and avoiding serious impediments to the implementation roadmap.

Moving Forward

The next key concept for adopting SAFe in Government is Aligning technology investment with agency strategy.

Next

Learn More

[1] How collaboration put a man on the moon. https://medium.com/@zeroagency/how-collaboration-put-man-on-the-moon-d21f9fb3ce8c [2] Katzenbach, Jon R., and Douglas K. Smith. The Wisdom of Teams. Harvard Business Review Press, 1992. [3] Developing high performing teams. The Center for Organizational Design. http://www.centerod.com/developing-high-performance-teams/ [4] 2017 State of DevOps Report. Puppet + DORA. https://puppet.com/resources/whitepaper/state-of-devops-report [5] McChrystal, Stanley (Retired General), et al. Team of Teams: New Rules of Engagement for a Complex World. Penguin Publishing Group, London, England, 2015.

Last update: 5 October 2022