By Brian Tucker, SAFe Fellow, Ivar Jacobson, Original Post

Our SAFe Fellow community is fantastic at bringing concepts together with examples. This blog by SAFe Fellow Brian Tucker is an exemplar of explaining a topic that can take a few rounds to understand and making it into something not only understandable but also fun to learn about. Brian was one of the first trainers outside of the Scaled Agile Academy to qualify as a SAFe Principal Consultant Trainer (SPCT), having worked with the Framework since its initial inception ten years ago. Brian has been involved in SAFe implementations at numerous companies across Europe, including Hybris, PZU, Ford, Nordea, NHS Blood + Transplants, Etihad Airlines, Sony Playstation, and LV Insurance.

Have a great read and a meaningful journey!

-Rebecca Davis and the Framework Team

On The Nature Of Portfolios

This series of blog posts, “On the Nature of Lean Portfolios,” is an exploration of Lean Portfolios. It is the thought processes running through my mind, exploring the possibilities so that I understand why things are happening rather than just doing those things blindly. It is not intended to be a fait-accompli presentation of the solutions within Lean Portfolios but an exploration of the Problems to understand whether the solutions make sense. There are no guarantees that these discussions are correct, but I am hopeful that the journey of exploration itself will prove educational as things are learnt on the way.

EPIC LIFECYCLE

Epics have a lifecycle, they don’t magically appear fully formed. There is work to be done to progressively elaborate a business case and if the Epic is approved then there is further work to progress the Epic through implementation.

Previous posts have explored the states that an Epic progresses through in its lifecycle, and we’ve stated how it is important to separate these states from the Process and the Work Products that are used to represent the Epic in the physical world. The separation of concerns allows both the Processes and Work Products to evolve to meet specific business needs.

In this post we’ll explore the Portfolio Kanban that visualises the lifecycle of an Epic and look at some of the decisions that influence the Epic’s progress through its lifecycle. In subsequent posts we’ll look at the processes that can inform those decisions.

There is an accompanying video available here.

THE PORTFOLIO KANBAN – NORMAL DECISIONS

Kanban Setup

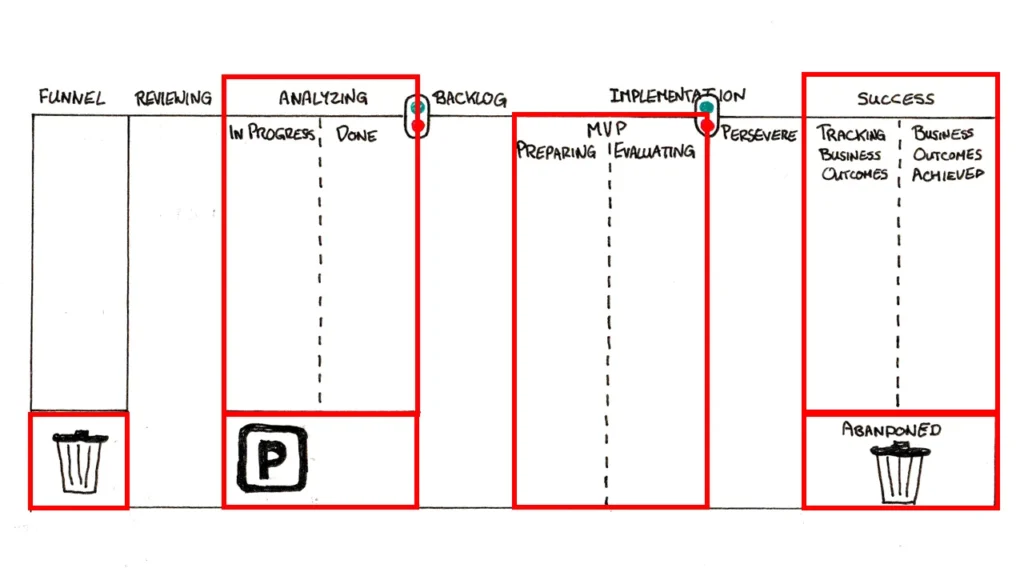

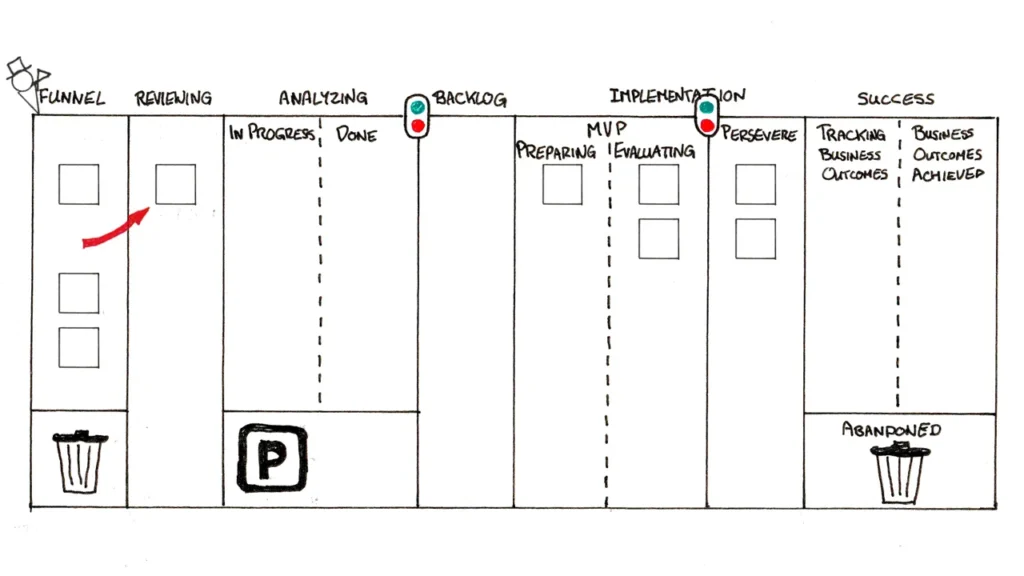

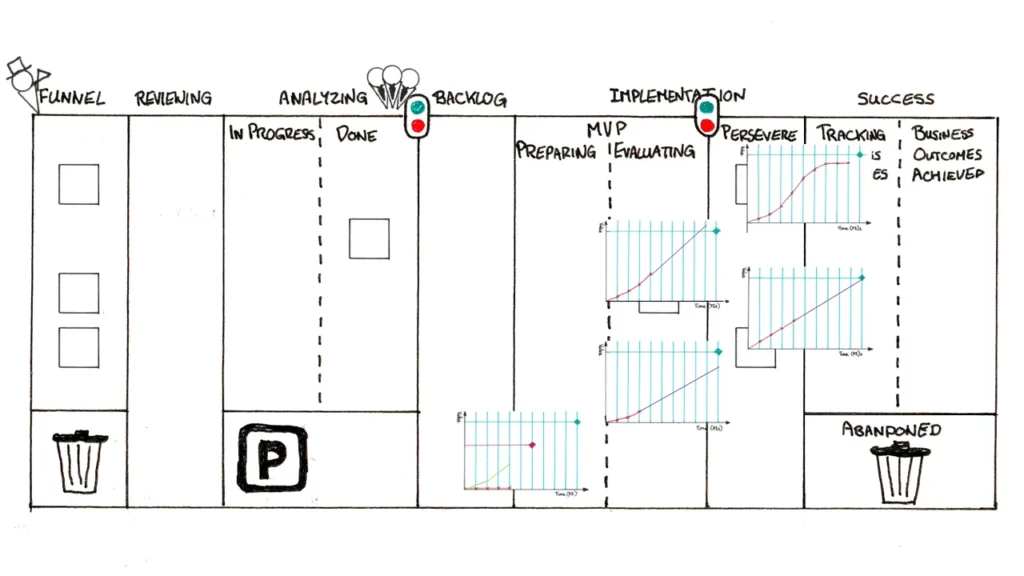

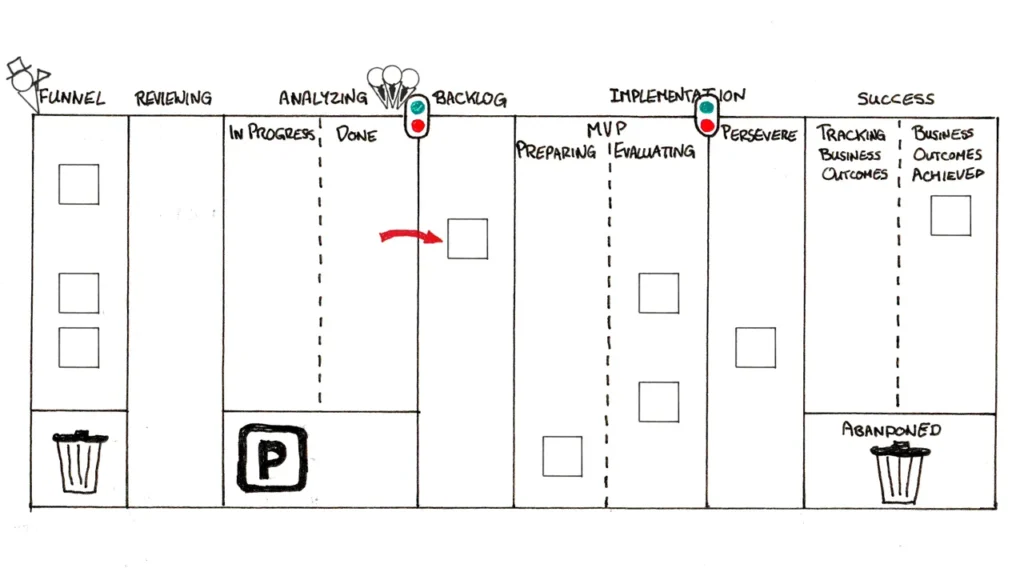

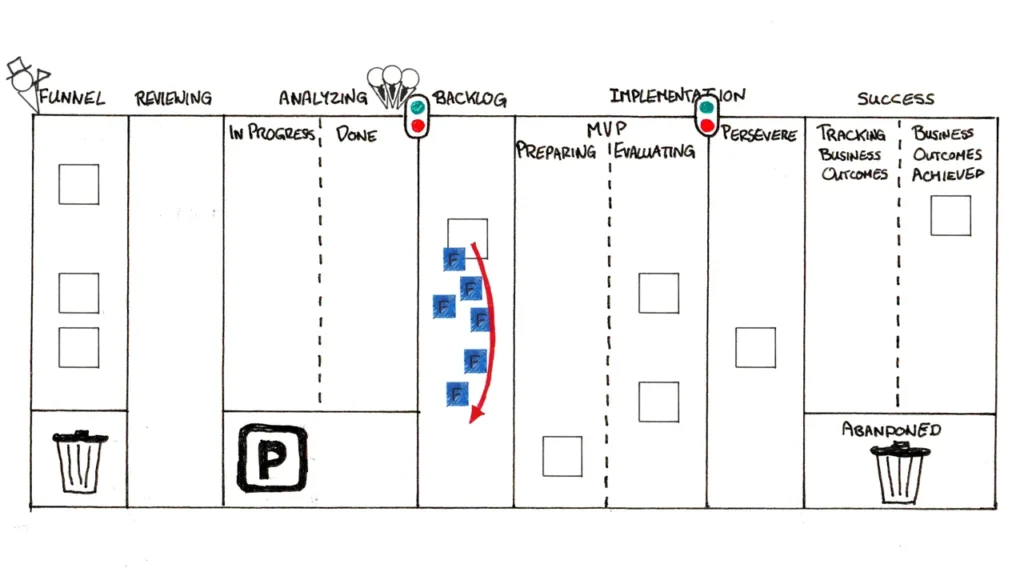

The first rule of Kanban boards is to make them your own. Map out your own process, not an idealised process from a slide. The default Portfolio Kanban doesn’t need a lot of changes but there are a couple of areas where a little extra information would help with managing the lifecycle of Epics.

The first adjustment is to the Analyzing column. There is a queuing point here; where Epics queue up, awaiting approval, the approval point being represented by the Traffic Signals at the top. It’s been split into In-Progress and Done to impose Work-In-Progress limits on the In-Progress column to ensure that too many ideas aren’t all being processed at once. It’s useful to see the queue building up in the Done column awaiting approval so that the queue can be actively managed.

Beneath the Analyzing column a parking lot has been introduced; this is for good ideas that have gone for approval but can’t move forwards for some reason. It’s another queuing point, making it visible allows the queue to be actively managed.

In Implementing, there is another split; within the MVP section, it is useful to know which Epics are still preparing for their first release and which have had their first release. First release is a key milestone, once a release is out the Business Outcomes should start moving. Prior to that point it might be possible to see some Leading Indicators moving; but the real goal is the Business Outcomes and they can’t move until a Release has occurred.

The final adjustment to Portfolio is to rename the Done column to Success and to split it into two. Epics should be Business Change, not just a “block of work to be done”; the Business Change is either Successful or Abandoned; whilst the work being done is important because it enacts the Business Change, the work is just a means to get that Business Change, it is not the primary measure. The outcomes from business change are often lagging; the profits and the money build up slowly, often a long time after the engineering has been completed. The Tracking Business Outcomes section of the Success column allows us to show that the engineering is “Done” but we can’t yet declare that “Business Outcomes Achieved” because the Business Outcomes are still building up. These columns equate to the Extracting and Successful states in the earlier blog on Epic states.

Finally, unlike most Kanban boards where once an item enters the board it makes its way across to the far side, this board has a habit of dropping things off the bottom. Not all ideas are worth pursuing; some get sent to the Trash Cans in the corners. This can happen at any time; “Ignore Sunk Costs” even in the implementing phases post-approval. The trash can on the left tends to be for Epics that never passed Approval, and the trash can on the right is for Epics that were attempted but weren’t Successful.

It’s the ability to stop work, even work in progress, that differentiates a Lean Portfolio from historic Portfolios. The goal of Lean is “Value in the sustainably shortest lead time” and if any idea, big or small, fails to demonstrate that it’s valuable then it should be stopped so that the money and effort can be redirected towards an idea that could generate value. The goal of the Portfolio is to stop the work before it moves too far right. Every time an item moves to the right the amount of time, effort and money being invested increases by a significant factor.

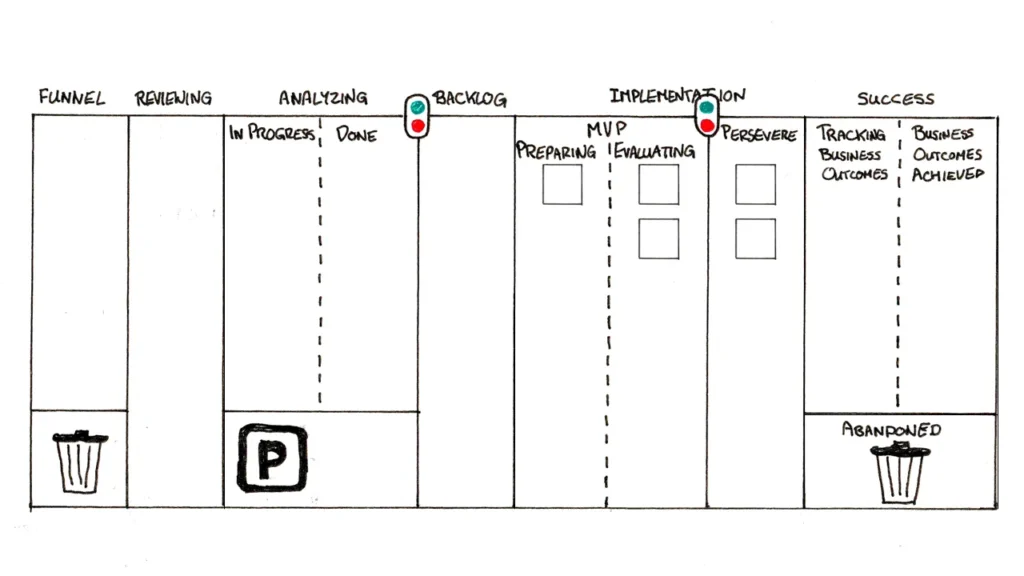

Most portfolios are in running state, there are already Epics in play. For this scenario there are 5 Epics spread across the sub-columns within the Implementation stage.

Ideas

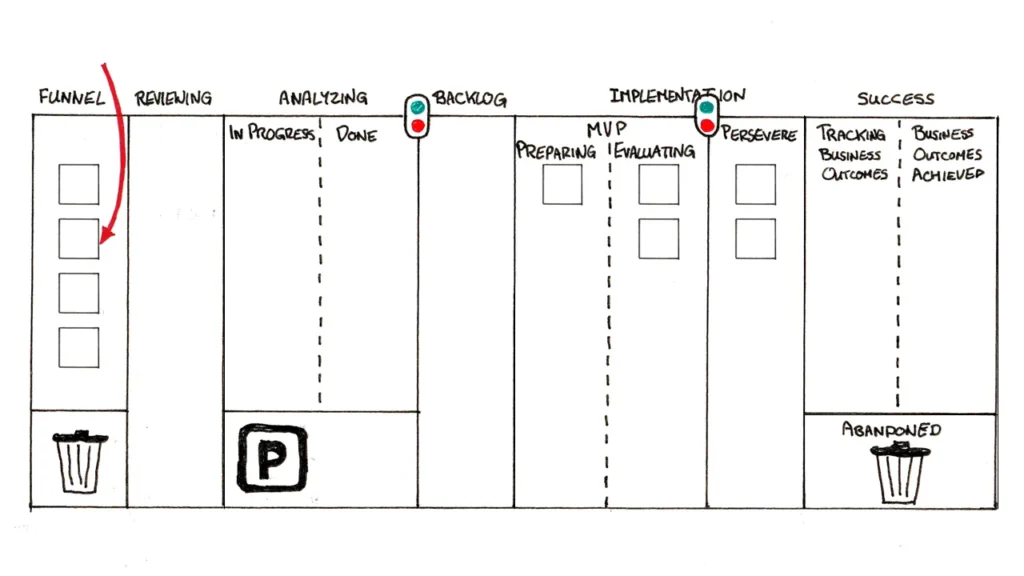

Ideas come into the funnel.

Should there be a Work-In-Process limit on the funnel?

No. Don’t turn ideas away because the one idea that you turn away will be the idea that heads off down the road and makes someone else rich. However, if there is an open-door policy for ideas, then there needs to be active management of the Funnel; otherwise, it will very quickly become a mess. It needs to be owned. For the purposes of this walkthrough the owner of the funnel will be called the “Director Of Innovation and Parties”; it should be noted that this is NOT an official SAFe term, never select this option in a SAFe exam!

Why the Director Of Innovation and Parties? Where do you think all the innovative ideas come from? A good party!

Whilst this name is just a bit of fun; there is some seriousness behind it. The social aspect, the parties, have importance psychologically later in the process but also Steve Johnson, Where do good ideas come from; the ideas of the Enlightenment were born in the Coffee Houses and Salons of Europe in the late 18th Century. In afternoon parties with genteel rules. Sometimes, good ideas occur when people connect with each other and a fragment of an idea gets picked up by others and then elaborated into a more fully formed idea.

The Director Of Innovation and Parties needs to be an expert at whatever it is your company does. What do I mean by experts? Read “Blink” by Malcom Gladwell. Malcom Gladwell talks about experts being people that instinctively know when something is right or wrong.

Usually people think of the art world. The expert walks up to the painting, stares at it, and declares:

A lost Rembrandt. A once-in-a-lifetime discovery

or

No, no, no. This is fake; any fool could see that

That initial assessment is often backed up with detailed scientific analysis but their gut instinct is usually right.

The Director of Innovation and Parties needs that same level of instinctiveness, because as the ideas come through the open door that is The Funnel, they will need to use that gut instinct to quickly decide what to do with the idea. Analysis takes effort; we only want to analyse those ideas that really need it, gut instinct will have to suffice for the rest.

Normal Lifecycle

This will follow the lifecycle of a fairly standard Epic and look at how the decision making influences it’s progress; the next blog will look at some of the alternatives that the Portfolio might encounter.

Standard rules of Kanban apply. If there is space in the Reviewing column then the Director Of Innovation & Parties, collaborating with other Portfolio Stakeholders, can select an Idea and start it on its journey.

The ideas coming into the backlog will have arrived in any old form, probably on the back of a napkin from the bar that the party was being held in. It is in Review that the Epic Hypothesis Statement Template is created. Every Epic that has passed beyond this point has the same Template as a header allowing us to compare them.

With the creation of the Epic Hypothesis Template the Idea takes on the form of an Epic. The further right an Epic has progressed, then the more data that it will have accumulated to prove the Hypothesis; better estimates and forecasts or even actuals once the Epic is in Implementation.

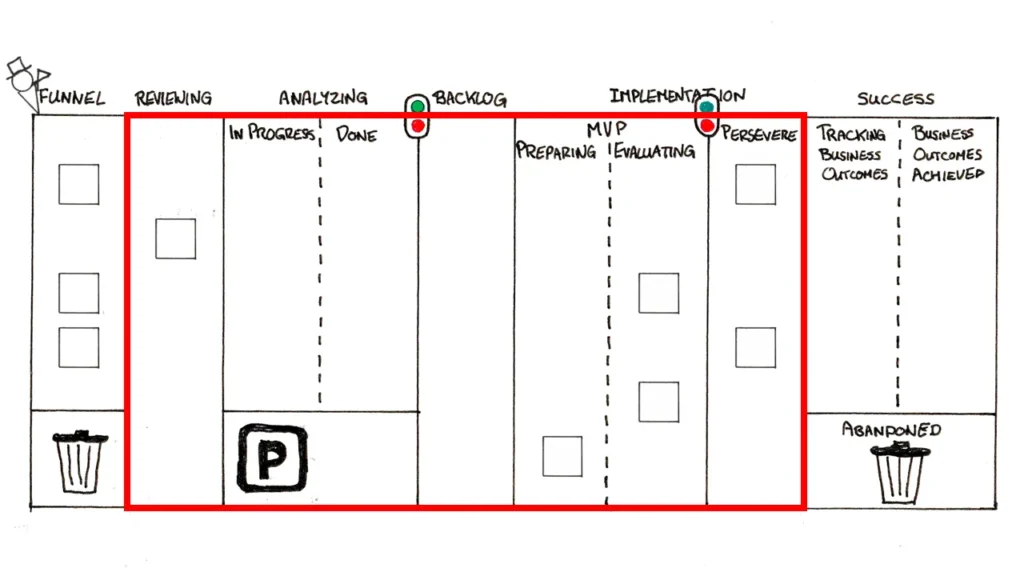

Now that the Epic is in a standard format we can start comparing; we can do a WSJF across all of the Epics from Review through to Implementing, all those Epics that are being actively supervised. We need an absolute priority across the whole set because we need to know if any of the new ideas are more valuable than the existing work. If they are then maybe we should try to get them into development and realise their value.

As we’ve seen from previous blog posts Portfolio WSJF is hard; WSJF across Features at the Agile Release Train level can be simplified because Features have to fit within the timebox that is the Planning Interval, which in turn allows Effort to be used as a proxy for Duration. We are also more likely to see multiple trains contributing to the same Epic, which could get it done quicker, but you are equally likely to see trains having to service multiple Epics within the same Planning Interval; therefore, work is happening in parallel, and it will happen slower.

The Director of Innovation and Parties facilitates a prioritization session, there is now an absolute priority across the set.

The new Epic happens to be more valuable than some of the Epics that are already in play; perhaps there should be an effort to get it into implementation sooner rather than later. Remember, what differentiates a Lean Portfolio from other Portfolios is it’s pursuit of value; this idea is more valuable than the others, Ignore Sunk Costs and Pivot Without Mercy or Guilt!

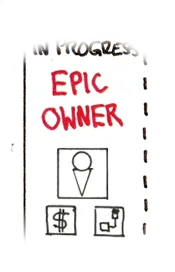

Officially, the Epic Owner is assigned in Review to assemble the Hypothesis Statement Template.

If there is space then the Epic can move into Analysis ands that is where the Epic Owner’s job really begins. Their job is to organise the business case and technical impact analysis.

The Epic owner doesn’t need to generate all of the information themselves, indeed some of the necessary information might be beyond their area of expertise, instead they will have to liaise with Sales, Marketing, Enterprise Architecture and many others in order to get the information generated.

Epic Owners need to be well connected within an organisation to collate the relevant information. Drawing upon the engineering community for the Technical Impact analysis; this analysis will influence the cost/effort estimates, a beige box beneath a desk has a very different cost profile compared to a Netflix style massively distributed cloud system. Drawing upon Sales and Finance for estimates around the returns that could be expected if this idea works.

Epic Ownership is probably the closest you get within the Framework to old-school Project Management. But unlike old school projects that brought together work and people; Epics are just the work. Epic Owners have no people to order around; they have no money to bargain with; instead they need to persuade the Product Managers and other Stakeholders that the Features from their Epic should consume the investment that has been made in the Development Value Streams and the Trains within them.

The goal is to do as little as possible for the business case; anything extra becomes waste if the idea isn’t approved.

Analysis done the Epic is queued waiting for the next Strategic Portfolio Review meeting.

There should be tight WIP limits on the In-Progress column in Analyzing and you want to keep a close eye on the queue of items in the Done column that are awaiting approval. I have seen organisations with a hundred business analysts all coming up with new ideas; preparing business cases taking them approval but the organisations only have engineering capacity to deliver a fraction of the ideas being suggested. That didn’t deter the analysts, they go running back to the funnel and start processing the next idea. The organisation was wasting huge amounts of effort and money analysing ideas that could never be realised.

Making the whole process visible end-to-end through the Portfolio Kanban makes it easier to spot when things are going wrong.

Lean Portfolio Management; the group of senior executives in the organisation that are ultimately responsible for the success of the Portfolio. They need to ensure that there is a coherent business strategy and that the work being done lines up with that strategy. As such, they are the ultimate content authority, and the Epics they approve heavily influence the work that the Trains and Teams are doing.

They need to consider the business case and decide whether their organisation should continue to pursue this Epic.

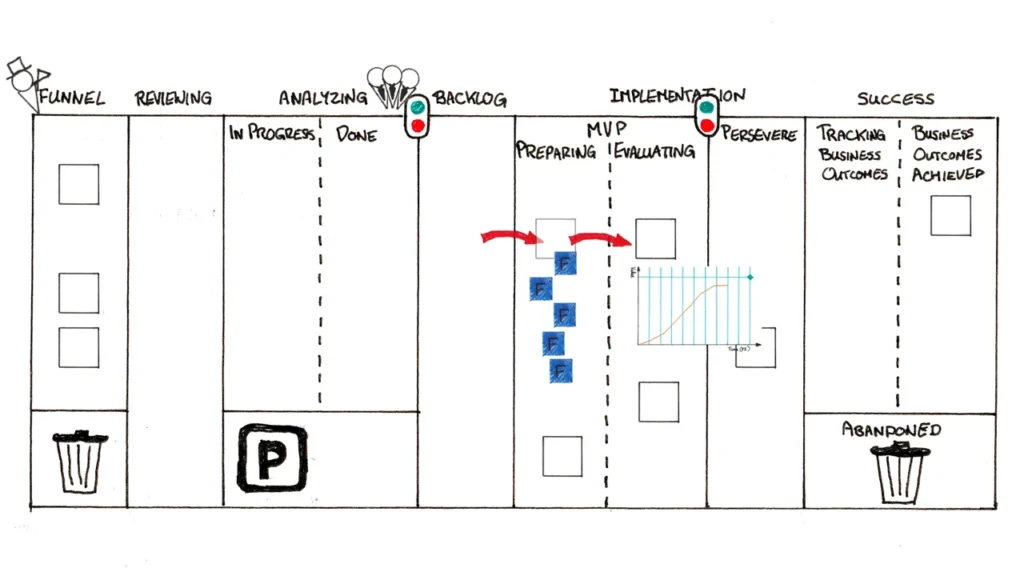

Green light, they said yes.

They approved the Epic; they’re going to want people to start working on the Epic, but…

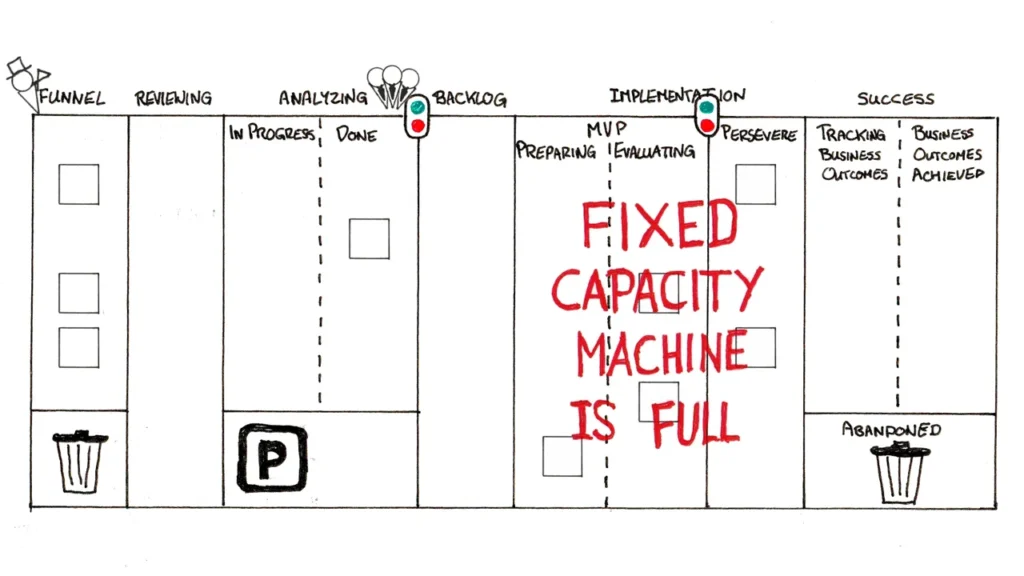

The organisation is a Fixed Capacity Machine and the machine is already full handling the existing approved Epics.

If the Lean Portfolio Management want this Epic then they need to do something. They need to clear some space and make capacity available.

They need to look at the metrics of the Epics already in Implementation.

Every Epic will have Business Outcomes and Leading Indicators that are being tracked; look to these to determine which ones to stop in order to create space.

For the purposes of illustration the diagrams show just one line; in reality most Epics will have a number of Business outcomes and Leading indicators that are being tracked.

Metrics have been discussed as part of Epic Feedback loop, what follows is a summary of the types of conversations that could occur.

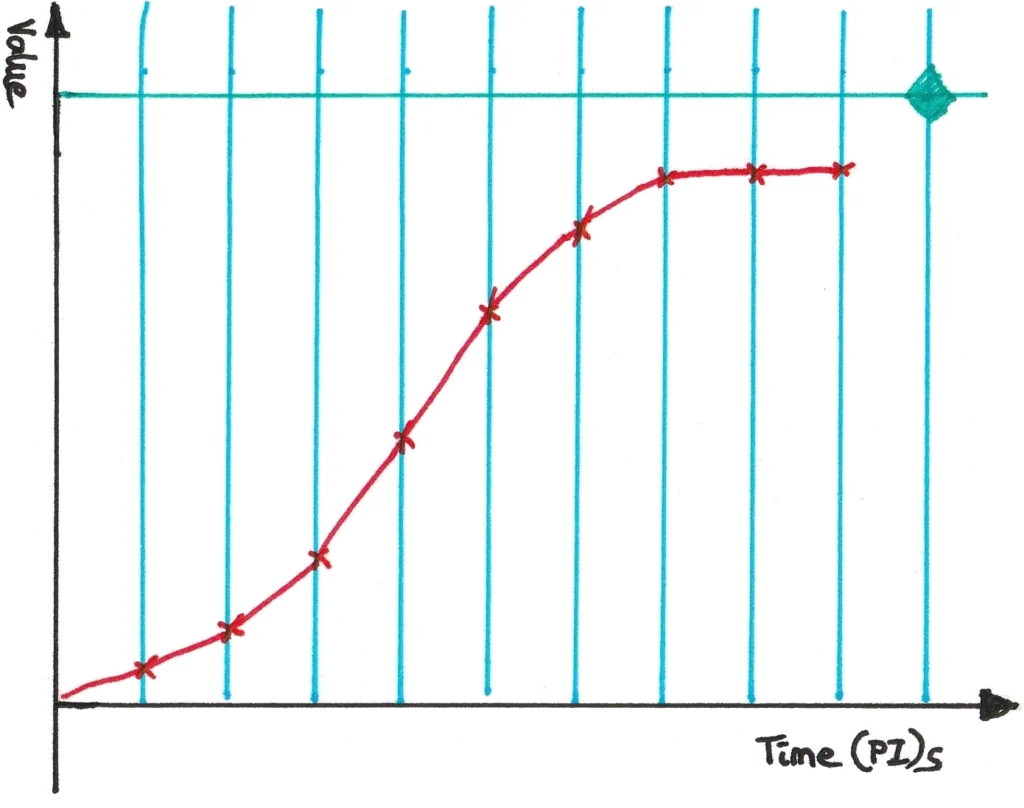

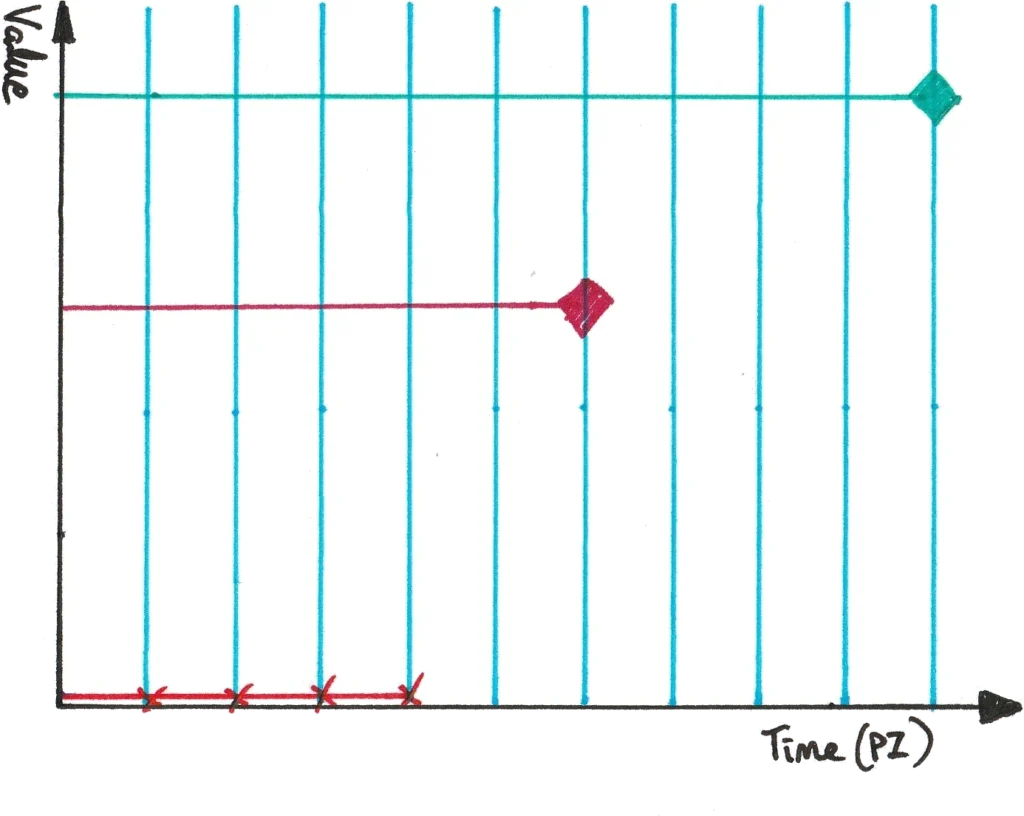

The Epic has almost achieved its Business Outcomes, but it’s been flatlined at 90% of its target for 2 PIs, with one more PI before its target deadline.

Have you ever asked the business people what the error margins are on their business target estimates? They’re about as accurate as our Effort estimates, and we all know how accurate our Effort estimates are!

That we’ve got within 90% of a target that was pulled from thin air isn’t bad.

It could cost more to close the gap than we would get in return, in which case, closing the gap doesn’t make economic sense.

Could victory be declared early?

Sometimes you don’t have a choice; if this was a regulatory issue and the Business Outcome is tracking the percentage of the company that is compliant then we’re going to have to close that gap no matter what the cost.

In this instance it’s a sales target and the results are close enough to declare success.

What do we do now?

Celebrate, have a party!

One of the Kotter Change Principles is: Generate short-term wins. So, celebrate those successes, consolidate the gains, and produce more wins.

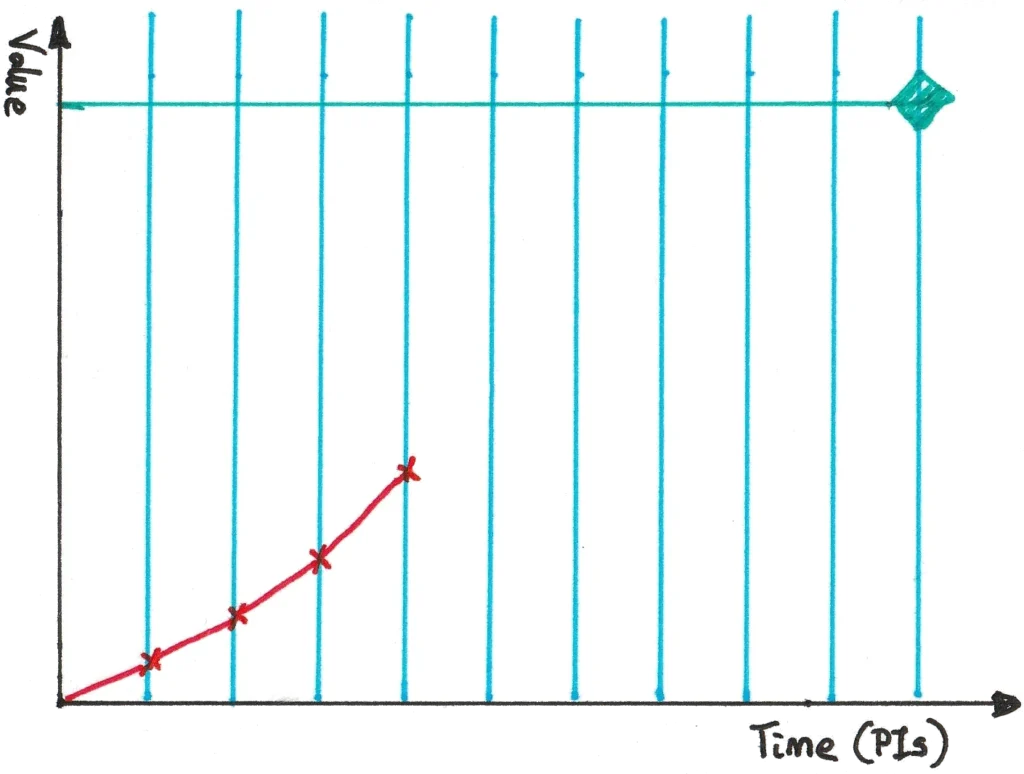

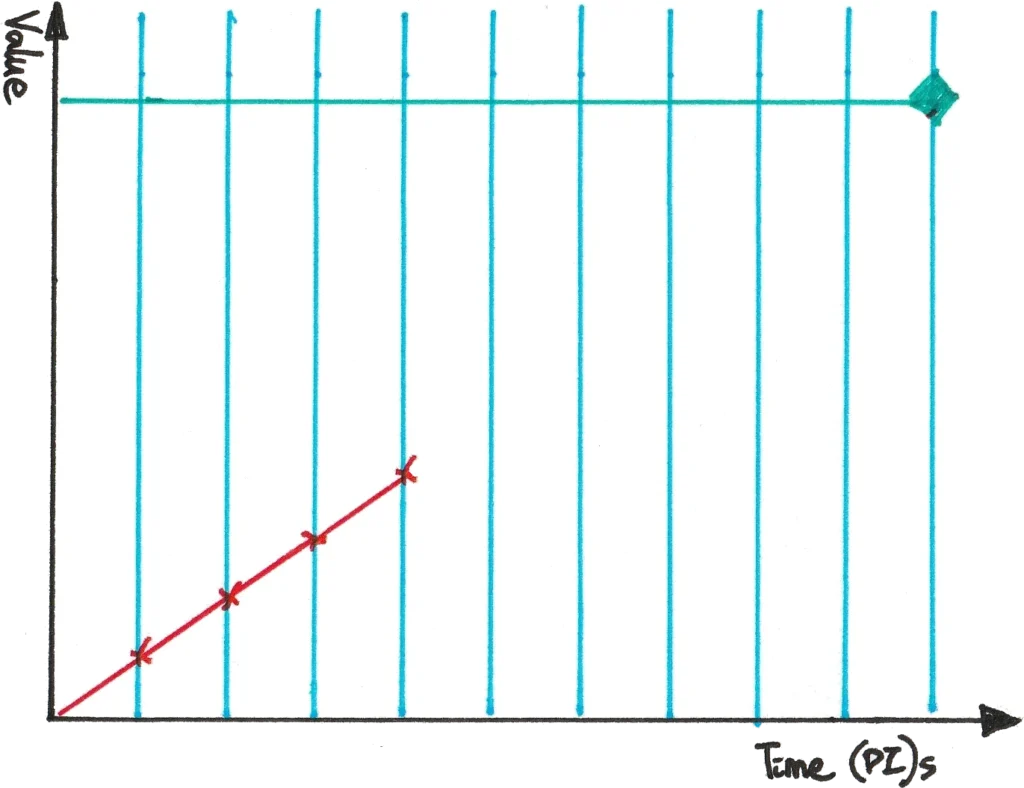

Most development endeavours follow a bit of an S-curve; slow to start, pick-up pace, trailing off again towards the end.

This one has just started its upturn. If we do a simple linear interpolation based on the last PI, the forecast shows it is coming in two PIs early. It’ll probably tail off, but it’s doing well at the moment.

Keep going?

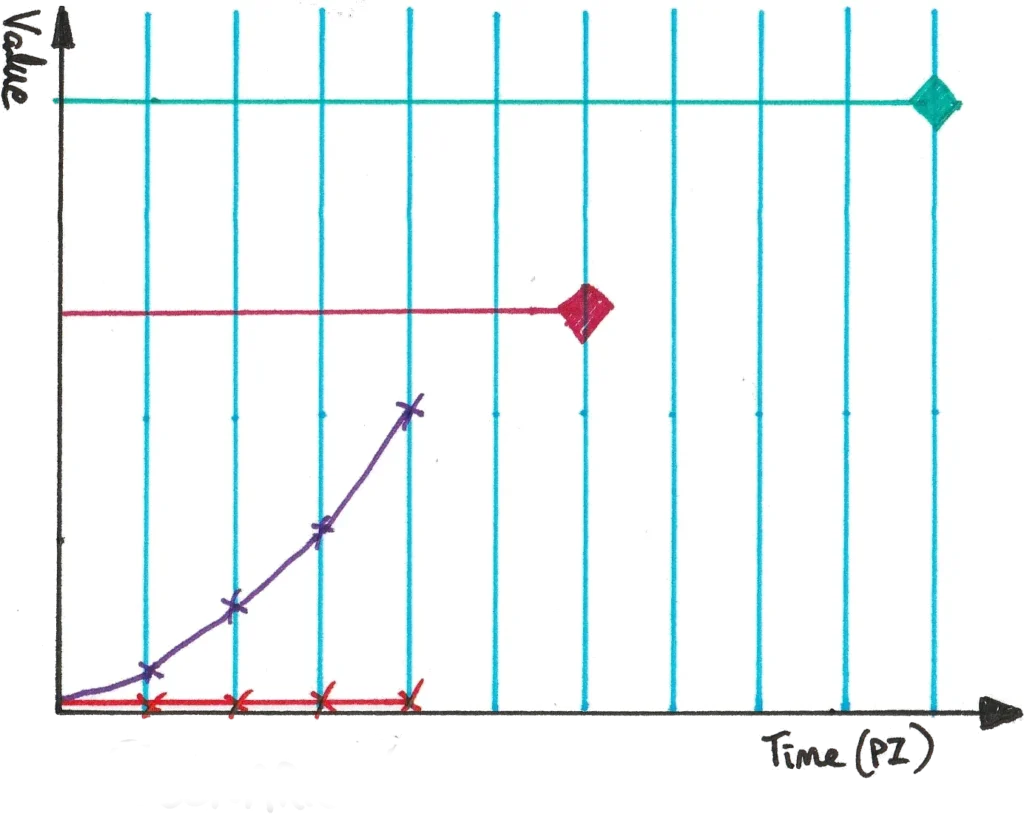

This one hasn’t reached the upturn yet.

If we did the interpolation then it’s not going to hit it’s targets within the expected timeframe; but it’s still early days.

Perhaps give this one the benefit of the doubt for another PI, but if it hasn’t started its upturn within the next PI, is it just a failing Epic? Do we need to cut our losses?

The forecast here is perfection, it’s going to hit it’s targets; delivering at exactly 3:44pm on a Thursday afternoon in 15 months time.

Are any alarm bells ringing?

I’d be suspicious that someone is making the numbers up; if the numbers look too good to be true, they probably are. This is a naturalistic system, and nature abhors straight lines.

Perhaps this is one of those watermelon endeavours? All green on the outside but crack it open and there’s a red and squishy mess on the inside. I would want to get inside and find out what is really going on.

Three PI’s in, no release, the business outcomes are still at their starting point.

What are you going to do? Are you going to cancel it?

What if this was a System Replacement Epic. No business outcomes will be visible until all of the functionality is present and the new, replacement system can be swapped in1.

This is where Leading Indicators come in handy, they can show that progress is being made when the Business Outcomes aren’t moving.

The green line shows a Leading Indicator: the number of functions that have been replicated and validated in the new system. Remember Agile Principle #7: Working Software is the Primary Measure of Progress. Our leading indicator in this particular example should honour Agile Principle #7 by demonstrating working, tested software.

This Epic can keep going for now.

All of this is SAFe Principle #1 at work; Take an Economic View. Use the numbers from the Epics to drive the decision making process.

A lot of these Business Outcomes are not easy metrics; they don’t come straight from engineering teams’ tooling. These metrics need to be obtained from Finance departments, from analysing sales statistics, and from running surveys, all of which are the responsibility of the Epic Owner. Their role doesn’t end once Approval has been sought; they’re working harder than ever to provide Lean Portfolio Management with proof that their Epic should be allowed to continue, as well as negotiating work into the Trains.

If capacity and budget are now available, then our idea can make progress, and it moves into the Backlog.

It’s worth noting the it might be possible to free up capacity and that capacity can’t always be used because budgetary constraints may mean that the capacity should be used on a different category of work than our idea. Hence the need for both capacity and budget. Also, the capacity that is being freed up needs to have the appropriate skills to take on the new work; there’s no point freeing up a bunch of Mechanical engineers when you need Software expertise.

Approvals and cancellations need to happen with enough time for the Trains to be able to process those decisions. Typically, Epic approvals happen near the middle of a PI.

Progress tracking of the Epics should be happening more regularly; probably every sprint. Lean Portfolio Management should meet at least weekly for Impediment removal. The premise behind Jeff Sutherland’s Scrum@Scale is the speed with which decisions can be made in an organisation; there is a high correlation between decision making speed and success of organisational endeavours.

Trains should be looking to the Portfolio Backlog and asking which Epics do we have to create Features for in our backlogs in order to move those Epics towards their business outcomes.

This is the “Pull” mechanic at work that balances demand and supply. Epics should not to be pushing work down onto the trains as it will break the system. That said, Epics Owners can’t be passive they will need to out there “Pushing” for the Product Managers in the trains to “Pull some features” from their Epic but they are competing for space in the backlogs with the other Epics and their Owners.

A clearly prioritised list of Epics helps those negotiations. Anything stuck in the Backlog for a significant length of time means that its Features just aren’t getting prioritised; consider abandoning it as other things are more important. This is the “Until WSJF determines otherwise” scenario that SAFe discusses as part of its Lean-Startup approach for Epics.

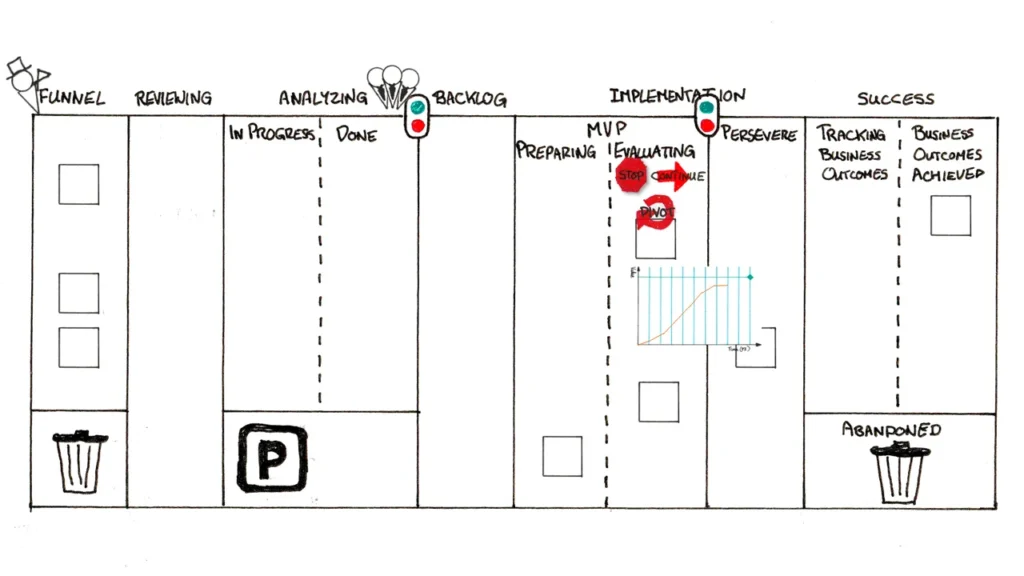

Once Teams and Trains have made a commitment at PI Planning to deliver some Features for an Epic then it can be said to be Preparing the MVP as part of Implementation.

The Epic is preparing for a First Release; features are being implemented.

Once a Feature for this Epic has been released then the Epic is in Evaluating.

Features continue to be created to try to prove the MVP.

Customers could start using it, therefore the Portfolio can start tracking the Business Outcomes.

At some point, the hypothesis of the MVP will be answered, yes or no; Lean Portfolio Management needs to make a Pivot or Persevere decision.

They could:

- Pivot and ask for a successive MVP to be evaluated

- Stop the work.

- Persevere if the hypothesis has been sufficiently proven

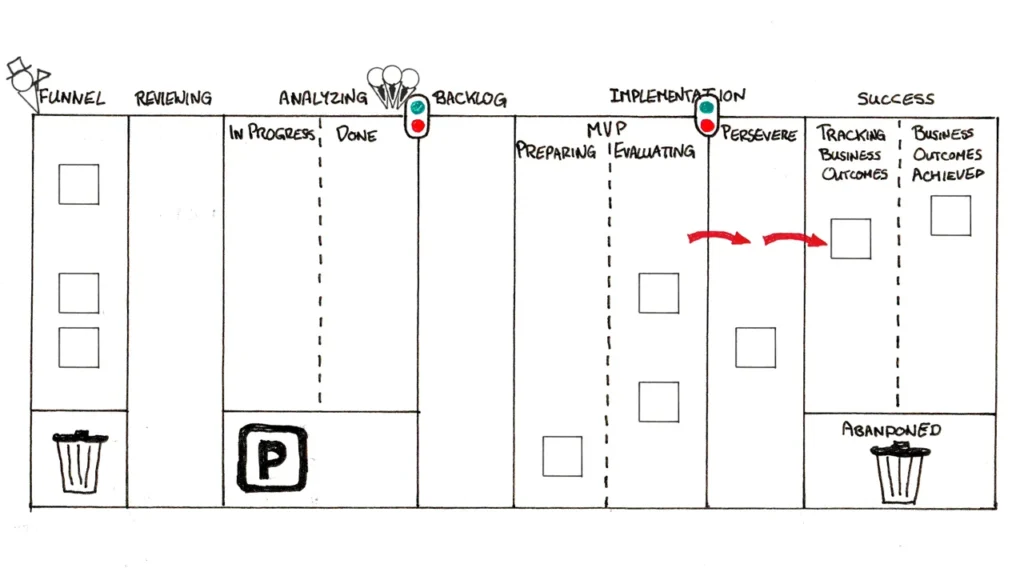

If the Lean Portfolio Management decide to Persevere then the Epic can move on. Features continue to be created to try and improve the Business Outcomes further. The metrics continue to be tracked and if the metrics aren’t good, or this Epic’s Features are not being prioritised because the Features from other Epics are more valuable, then it might be time to stop active management of the Epic and declare the Engineering Done.

Stopping active management means that the Epic is no longer requesting changes be made to systems; the Value Streams that own the systems have responsibility for any ongoing maintenance and support required.

But, it might not be possible to declare success just yet. The true Business Outcomes are often lagging indicators hence this Tracking Business Outcomes phase where the Business Outcomes might still be building.

Eventually, the Epic is close enough to its targets that Lean Portfolio Management can declare Business Outcomes Achieved.

If they’re happy; we should celebrate!

It’s that Kotter principle at work again. Everyone likes winning.

That covers the lifecycle of a standard Epic and the decision-making that influences its progress. In the next posting we’ll explore some of the alternative scenarios that the Portfolio Kanban might need to deal with.

#1 I would hope that the architecture of the replacement system is such that it is capable of being upgraded incrementally in the future. Let’s not make the same mistake a second time!