Participatory Budgeting: Understanding Color of Money and Other Constraints

By Luke Hohmann, Chief Innovation Officer, SAFe Fellow, Applied Frameworks, Inc. & Nikolaos Kaintantzis, Enterprise Agile-Coach & SPCT, Kegon

Note: This article is part of the Community Contributions series, which provides additional points of view and guidance based on the experiences and opinions of the extended SAFe community of experts.

Introduction

Participatory Budgeting (PB) is a collaborative process used in Lean Portfolio Management (LPM) for allocating the portfolio budget to its value streams. The most straightforward application of Participatory Budgeting involves allocating the budget equally among participants and asking them to fund the initiatives that participants believe are most likely to achieve the portfolio’s objectives.

The underlying assumption in this application of PB is that the money being used to fund initiatives is free of any constraints in how this money is allocated and that the portfolio team can reallocate money as desired.

However, there are many applications of PB in portfolios that have funding allocation constraints. For example, a Non-Governmental Organization (NGO) operating across many countries may have legal constraints that require money raised for a philanthropic purpose in one country be spent only on projects within that country (a geographic constraint).

For-profit enterprises with different legal entities within the same portfolio may be structurally constrained to only fund Epics by each legal entity (no pooling of funds) as opposed to having Epics funded by multiple entities (a legal entity constraint).

The unfortunate consequence of assuming that PB is free of any constraints in the allocation of funds is that some enterprises avoid using PB, depriving them of the benefits of PB.

In this article, we describe how PB forums can be designed to accommodate a variety of common constraints, expanding the use of PB within and across enterprises. These improvements can increase alignment, portfolio flow, and create new opportunities for enterprises to fund the most important Epics.

Common Constraints

We begin with a discussion of common constraints that impact the portfolio and then explore constraints within and between portfolio elements, such as constraints between funding a value stream and an Epic or constraints between Epics.

Regulatory Constraints Influencing Portfolios

Each funding source or account may have specific rules or regulations that govern how the funds can be allocated and spent. These rules can include restrictions on the types of activities or programs that can be supported, the timeframe within which the funds must be used, or limitations on the recipients of the funds.

Two common regulatory and policy constraints that influence the allocation of portfolio budgets include:

- Earmarked Funds. An earmarked fund means that money has to be spent for the purpose it was raised – the members of the Strategy and Investment Funding team are not allowed to spend it on something else. An example might occur in government when taxes are raised for education: these funds cannot be spent on military infrastructure.

- Spending Regulations. Private foundations based in the United States are required to spend a certain amount of money or property for charitable purposes, including grants to other charitable organizations (see US IRS Regulations). The amount that must be distributed annually is ascertained by computing the foundation’s distributable amount. The distributable amount is equal to the foundation’s minimum investment return with certain adjustments. Failing to adhere to these restrictions can cause the loss of non-profit status.

Collectively, these kinds of constraints are often referred to as the ‘color of money’ and refer to the categorization or classification of funds to different funding streams or accounts within a government budget based on their intended purpose or restrictions. It is a way to differentiate and track the various sources and uses of funds within a budget.

The term ‘color’ is used metaphorically to represent the different categories or classifications of funds. Different colors are often assigned to indicate the specific purposes or restrictions associated with each funding stream. For example, funds allocated for defense might be considered ‘green money’, while funds for education could be referred to as ‘blue money.’

SAFe Fellow and Methodologist Dr. Steve Mayner notes that the classifications associated with the ‘color of money’ can be quite complex. For example, in the United States, funds may be appropriated for a specific theme or objective and then allocated to agencies, sometimes with very specific usage requirements. These may appear as a line item in a budget (‘weapons systems’) and at other times as a single IT budget that is further redistributed to various programs. These funds can have additional rules, such as funds that can only be spent on R&D, funds that can only be spent on maintenance, and funds that must be spent within a fiscal year or across a number of fiscal years.

By identifying funds with specific colors, the LPM function can more easily track and manage the allocation and expenditure of funds according to the intended purposes and restrictions. It helps ensure transparency and accountability by providing a clear framework for budgeting and financial management.

It is important to note that the term ‘color of money’ is a metaphor. Operationally, finance experts should design a meta-data tagging system that enables business leaders to track budget forecasts, allocations, and expenditures made by value streams against any constraints.

After the PB session, this meta-data tagging system should be shared with leaders who are managing Value Streams, Solutions, and ART backlogs. Finance experts can participate here by asking questions about the work to be done in each Feature and then providing guidance on what funding meta-data coding should be applied to that backlog item (in the US government, that is captured in a funding code that has about 30 digits!).

Once that code is included as metadata in the backlog item in whatever ALM, then it moves forward with awareness, and the funding data follows the item through the entire lifecycle. Filtering, searching, and reporting can all be done on those metadata tags for any type of governance or auditing activity. Similar meta-data tags are useful in the commercial sector, especially when tracking expenditures can be capitalized or when more fine-grained analysis of guardrails is desired.

Policy Constraints Influencing Portfolios

Unlike regulatory constraints, which are imposed on enterprises by external parties, policy constraints are self-imposed constraints. The internal organization can choose its degree of compliance, as the penalties for non-compliance are not typically as formal or rigid as regulatory constraints. Here are some examples of self-imposed policy constraints.

-

- Guiding investments by Horizon. The SAFe LPM guardrail of allocating a certain portion of the budget to each investment horizon is a recommended policy that promotes healthy investments across the portfolio.

A team engaged in PB may initially allocate funds in a manner that is inconsistent with the constraints or investment allocations targeted by the portfolio. For example, a portfolio may establish a goal of allocating 15% of the total budget to Horizon 3 Epics. During a PB forum, a given team may allocate too little – or too much – of the budget to Horizon 3.

When the participants in a PB forum realize they forgot or ignored the investment horizon guardrail, they will typically conduct additional rounds of investment. We discuss this constraint in greater detail later in this article.

-

- Balancing investments across strategic themes. Similar to investments by horizons, ensuring that each strategic theme has a certain portion of the budget is beneficial to ensure that the organization is formally investing in its strategy.

- Portfolio Epic Capacity Allocation Guardrails. Portfolio Epics are cross-cutting concerns that affect multiple value streams. When chosen, they can serve as a ‘tax’ on the allocation of funds to the value stream. For example, suppose the enterprise has established a strategic theme to expand operations in LATAM. One portfolio Epic that affects all solutions would be localizing solutions into Spanish and Portuguese. The funding is still given to the value streams, with the requirement that a portion of the funding will be spent to implement the portfolio Epic.

- Use it or lose it. In many government entities and in some companies, you have to spend all your budget money for a given fiscal year (or period) in the year it was allocated, or your subsequent budget will be reduced. While common in many organizations, we find that this policy leads to dysfunctional behavior, such as spending current money in a wasteful manner to preserve the future budget.

- Enterprise compliance. Organizations operating in regulated markets will often automatically require that compliance Epics are funded to ensure the business can sustain itself. This is common in financial and insurance markets or in chemical or process manufacturing, where compliance with data or safety regulations ‘must be funded’ for the business to operate. Even though these are framed as ‘required investments’, they are optional, as the enterprise could choose to pay fines or exit a business.

- Large enterprises with multiple portfolios. Holding companies often contain multiple and separate legal entities. For example, a multinational corporation will commonly establish multiple subsidiaries in the countries in which they operate.

The parent company can be modeled as a SAFe® Enterprise portfolio, and each subsidiary and be modeled as a separate SAFe Portfolio.

Constraints Between and on Funding Epics

Backlog management theory teaches us that the optimal structure of any backlog is that the backlog items are independent. This provides a number of benefits, including the ability to easily reprioritize the backlog or insert new backlog items in response to emerging conditions.

Backlogs in practice must account for the relationships that exist between backlog items. Accordingly, SAFe LPM must account for the condition in which there are relationships among Epics. The implication of the ‘color of money’ is that there are constraints on how a portfolio can be funded, both in terms of the source of funds and the use of funds. High-impact LPM practices broaden this scope to include constraints between and on funding Epis. This enables LPM practitioners to approach all of the constraints in a consistent manner.

In this section, we discuss constraints between Epics.

- Epic B requires Epic A

A required constraint exists between two or more items when one of them requires another to be funded. Example: If we want to do Epic B, we must do Epic A first. While this kind of relationship is more common between multiple Features, and while the LPM team should strive to design these relationships out of the Epics during the Analysis stage of the Portfolio Kanban, the reality is that these constraints may exist.

Note that this can enable leadership teams to better control how much they wish to invest in an Epic.

- Epic A excludes Epic B

An exclusion constraint exists between two or more items when one of them excludes another to be funded. Example: If we fund Epic A we >cannot fund Epic B.

- Choose one of Epic A or B, but not both A and BA mutually exclusive constraint exists between two or more items when one or none of them can be funded, but not all of them. Example: We can fund Epic A or Epic B, or neither, but we cannot fund Epic A and B.

- An Epic must be completed by a specific date

A market rhythm or market event constraint exists when a given portfolio Epic must be completed by a specific date. Examples include constraints imposed by governmental regulators or a Supplier, such as a requirement to upgrade ALL of the Solutions within a portfolio to comply with new regulations, such as the data transfer agreement reached between the US and the EU in July of 2023. Note that even if the required costs to comply with the regulation are low, the LPM team may still want to track the Epic as a portfolio Epic because of the strategic importance to the organization and the potential for negative consequences if the Epic is not completed by the required date.

Designing PB to address constraints

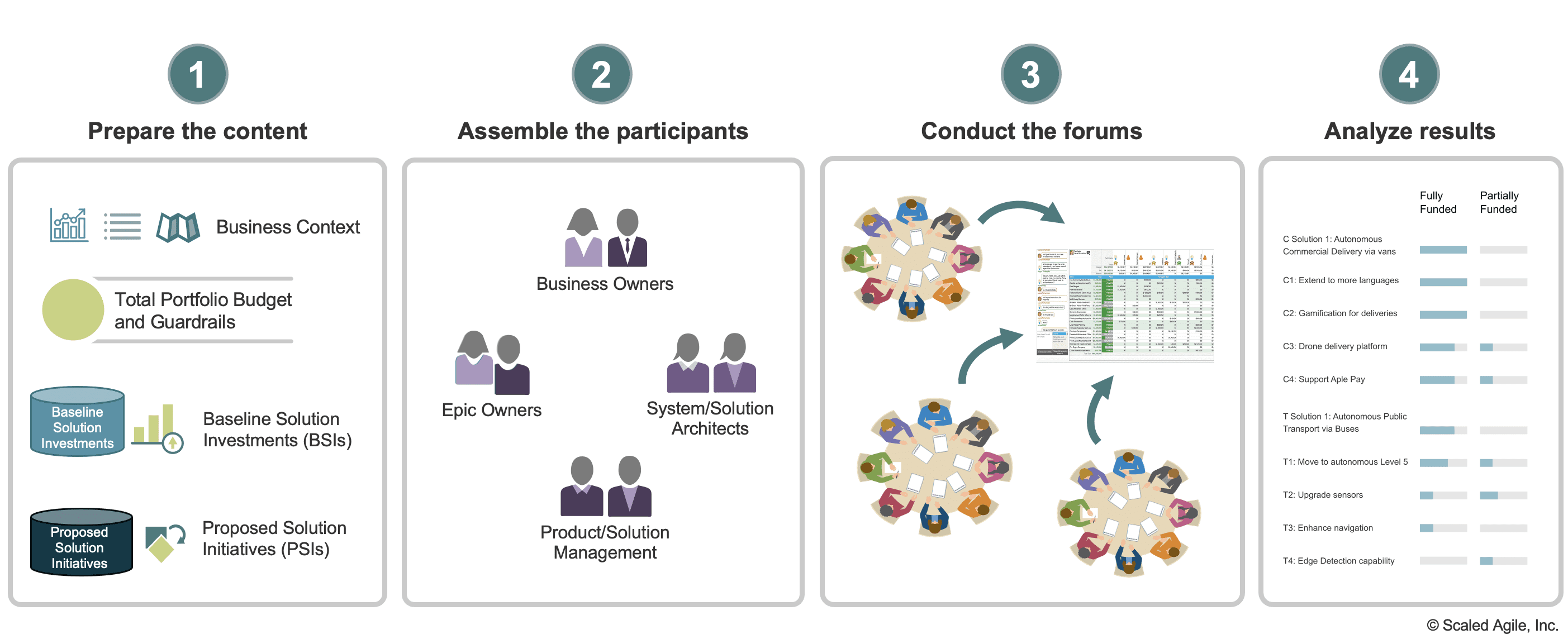

The core process for PB, described in the Participatory Budgeting article in SAFe, is embodied within this graphic:

The key changes we make when dealing with the constraints and ‘color of money’ are in steps 1, 3, and 4.

Preparing the content and understanding the constraints

During the development of the content, we examine the source of the portfolio budget for ‘color of money’ constraints and each Epic for Epic constraints (such as how this Epic relates to the color of money). The primary goal of this phase is understanding the constraints. We decide how to deal with these constraints in a subsequent step.

- Color of money constraints. The nature, type, and impact of each color of money constraint must be identified. We (the authors) typically capture these in a spreadsheet that identifies the source of the funds (such as a government agency) and the constraints associated with this money. The specific manner in which you capture these details should be aligned with the infrastructure you’re using to support PB forums. Be careful to include the magnitude of any constraint and how the constraint is calculated. For example, some constraints are expressed as an absolute number: you must spend at least this much money, or you cannot spend more than a specific number. Some constraints are expressed as percentages, such as ‘25% of the budget must be spent on R&D’, which can cause fluctuations in the available budgets for specific items.

- Epic constraints. We augment the description of the Epics to include specific guidance on any constraints that exist between or on Epics. This is required so that all participants are given the same information during the forums. It does not have to be complex. For example, stating, “The updating of the security architecture requires first the migration to the cloud”.

- Identifying additional constraints. It is always possible that there may be a constraint identified that is not a color of money or a funding constraint on an Epic. For example, minimum or maximum funding constraints may exist when funding a joint venture with another company; or a constraint may exist in the timing of payments to Suppliers that impact the available budget for funding internal Epics.

After the rules are understood, the main question becomes: What should we do with the rules? Several options exist, depending on how much the constraints have to be obeyed. Are these rules hard or soft? Hard rules are designed into the process. Soft rules are managed through collaboration and instruction. Let’s explore these options in greater detail in the next sections.

Enforce constraints with hard rules

In this option, you will design your PB forums such that constraints with hard rules are enforced during the forum.

For example, suppose one Epic requires another Epic to be funded. Organizing this hard rule during the forum means that all forum facilitators will instruct forum participants that this rule must be followed within the forum. Practically, this makes conducting the forum a bit more difficult, as the flow of money and decisions with the forum are a bit slower.

When conducting an in-person forum, you can print money in different colors to represent the actual ‘colors of money’ constraint. This structure helps participants reinforce that ‘purple money’ can only be spent on ‘purple Epics’.

Manage constraints with soft rules

We see this often in classic PB, when participants are asked to consider investment horizon guardrails when allocating money for Epics. The rules are soft in that they’re designed with some flexibility for the participants.

To illustrate, suppose the LPM team has established a target of 15% of the budget for H3 investments. In preparing for the forum, this might be converted into a range of 12% – 20%. This approach ensures that the minimum investment criteria in H3 is honored while also allowing a given team to allocate a bit more than recommended for H3.

Soft rules often require multiple passes through collaborative funding. For example, in the first pass, a team might spend more time focused on H0 and H1 and forget about H3. When the first pass-through items are analyzed, the facilitator will point out that H3 has not been funded to the required levels, causing the forum participants to reallocate funds.

This process of allocating funds, discussing the impact of the allocations, and then reallocating funds based on new information is the heart of the trust-building processes that create the best PB outcomes.

Ignore constraints during forums

Because PB provides insight into how funds should be allocated, a PB forum can be designed to ignore all constraints, allowing the participants to fund their highest priority Epics and more thoroughly capturing ‘how people want to work’. This is considered a ‘classic’ forum of PB and has the advantage of maximizing the data acquired from the perspective of market research.

You can also mix and match constraints. For example, you can start the forum with a ‘fast play’ of PB without constraints. This helps familiarize participants with the content. You can then introduce a ‘slow play’ forum with constraints added. Comparing and contrasting the results of the constrained and unconstrained forums can create additional opportunities for leaders to address constraints through creative choices.

Adjusting the cost of Epics within forums

It is common for the PB Forum participants to seek to adjust the costs of Epics within a forum. For example, the participants may seek to lower the scope of an Epic, thereby lowering its cost. Alternatively, when the cost of an Epic has been misestimated, the forum participants may seek to raise costs to reflect a more complete understanding of the Epic.

While it can be permissible to adjust costs within forums based on agreements to change scope and/or new information that emerges during the forum, this must be done with considerable care. Doing this well requires the following:

- Make sure the individuals within the forum have the expertise to understand how adjusting scope may impact cost. For example, if the work is being done by an external Supplier, you’re making an assumption that the Supplier will come back with a lower bid.

- Changing the costs of Epics makes comparing the results of multiple forums more difficult, as different forums with items that have different costs will almost certainly produce different patterns of funding.

- Avoid lowering the cost to enable the funding of more Epics. Epic Owners are given the responsibility to develop a good-faith estimate of costs and benefits in the Lean Business Case. Changing these in the forum without involving the Epic Owner can lower trust and slow down decision-making.

Instead of adjusting costs within a forum, we recommend running at least one PB forum with stakeholders to help calibrate the costs. A single forum can quickly identify concerns with the costs of Epics that can be resolved by Epic Owners and ART leaders in advance of a larger set of forums.

Analyzing forum results

When a PB forum has minimal constraints, the analysis of the results is quite straightforward: typically, the LPM team will approve funding the items that have been most funded across all of the forums. This is described in the PB article and embodied within this picture:

Analyzing the results of forums with complex constraints highlights the interplay between the design of the forum and the challenge of post-processing. In general, the more the forums generate results that honor the constraints (hard rule design), the easier it is for LPM teams to analyze the forum results and make decisions.

However, as described earlier, hard rules do not generate the same kind of insights into the will and desire of the forum participants. Accordingly, the soft rule design option can be beneficial to LPM teams who seek to understand a broader range of motivations for funding choices.

There is a catch: If you ask the forums to apply the constraints, then the participants start to gain insight into the constraints that the Portfolio operates under, whereas if you don’t apply constraints the participants won’t gain that insight. Ultimately, you will gain different insights depending upon whether you ask the forums to apply the rules or whether you give the forums a completely free hand to spend the money as they like.

When analyzing the results of soft rule constraints, the LPM team must take care to keep track of their choices and develop a communication strategy that informs the participants as to why a specific set of funding choices were selected. For example, let’s say that LPM establishes a 15% funding target for H3 and that all forums consistently funded H3 to less than 10%, instead allocating more money to H0. In this case, the LPM team may choose to maintain H3 funding at 15% based on a longer-term or more strategic time horizon. It is the responsibility of the LPM team to make certain that these funding choices and the reasons behind them are clearly communicated to the entire organization.

Ultimately, the design of a specific set of PB forums is not only how we want to structure rules as ‘hard’ or ‘soft’ but also the degree to which we want to acquire information from participants to promote better decision-making.

Finalizing the Choices

The step in the process is making the funding choices across the Epics. Regardless of the PB forum design, the actual funding of Epics and Value Streams must honor all constraints.

Communicating Forum Results

Communicating the forum results ensures that all participants understand which funding decisions were made by the LPM team. This does not mean that the funding may match the results of the forums.

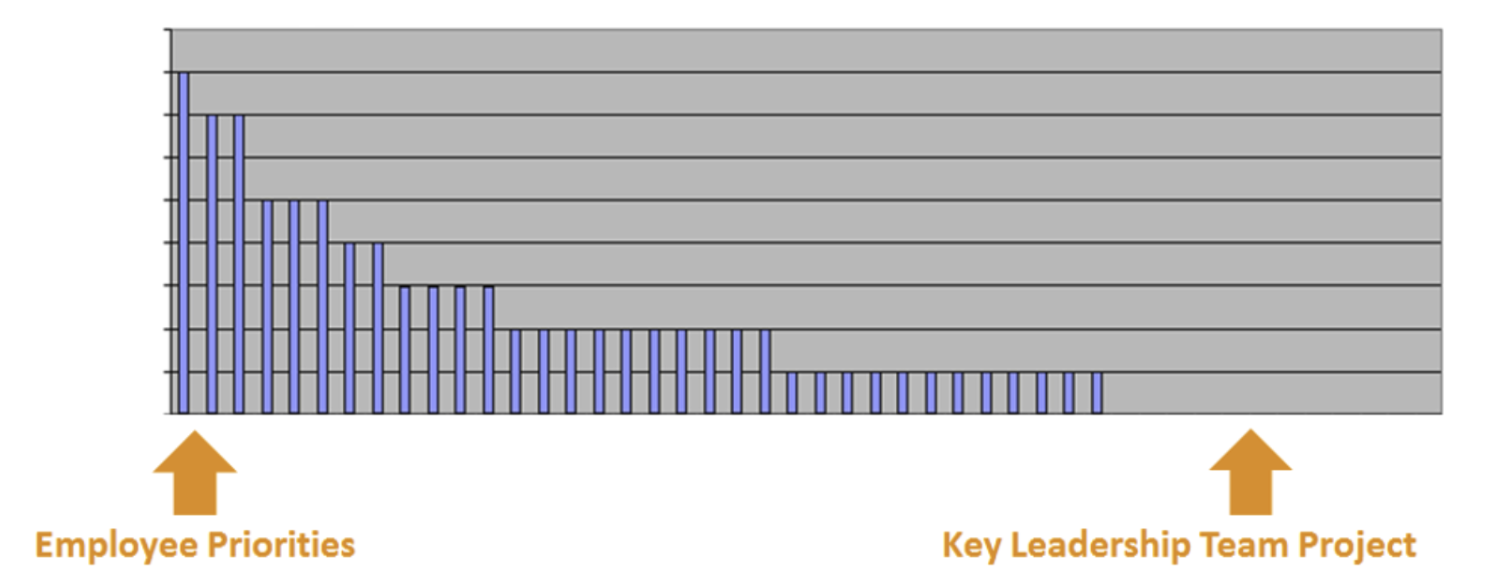

Consider the results from a Participatory Budgeting event at Verisign[1]. In this implementation of PB, we ran one forum with the leadership team and nine forums with the extended teams. As shown in the diagram, which captures the number of times each Epic was funded, we can see that an Epic that was a high priority for the executives was not chosen by employees in any of the extended forums.

The VeriSign leadership team was shocked by this result. Because they felt that this Epic was central to the strategic goals of the division, they were certain that employees would select it.

When presented with the data, the leadership team had a choice: skip the Epic or institute an education plan that more clearly articulated why they chose this Epic. The leadership team chose the latter and developed a thoughtful education plan that explained why this Epic was critical to release the portfolio strategy.

The education plan was a success! It increased trust within the organization, helped everyone realize that their leaders were not operating in a ‘command-and-control’ model, and reduced implementation time. As one employee stated, “If they had more clearly explained the connection between this Epic and our strategy before the forums, everyone would have funded it!”

Misuses, dysfunctions, and myths

Awareness of the constraints that may impact a PB session and LPM can unintentionally lead practitioners to a variety of misuses, dysfunctions, and even myths about LPM and PB. Let’s identify some of these so that we can promote healthy uses of PB while dispelling myths.

Misuse 1: Creating colors of money to fund an Epic

In SAFe, we finance the value streams, not the work items. Nevertheless, in some companies, portfolio leaders still stick to the idea that you have to ‘raise money’ to make an Epic possible. This is simply creating a ‘color of money’ constraint within a portfolio to try and coerce the portfolio team into funding an Epic.

Why is this, in our opinion, a misuse?

A key principle of PB is that the best Epics will be funded. They should compete with other Epics on their merits as much as possible. Accordingly, we do not advocate creating colors of money to fund specific Epics.

Misuse 2: Manipulative cost estimates

Each Epic in a PB session has a cost. For example, an Epic will include a cost for the proving or disproving of the Epic hypothesis. Inevitably, this is an estimate, and like all estimates, it can be created in a way that is healthy and reflective of best practices, or it can be manipulative.

For example, an Epic could be priced too low in order to coerce individuals into funding it. Alternatively, an Epic could be priced too high in order to convince individuals that it should not be funded.

A related manipulation is to promise more or fewer benefits than can be reasonably expected from the Epic or to avoid the development of leading indicators and other elements of the Lean Business Case.

The following strategies can help improve the estimation of costs and description of benefits.

- Use SAFe PB, as the social structure of PB means that a larger number of people will be reviewing Epics during the forum. This scrutiny naturally reduces negative manipulations of the price or the description of benefits because participants will not fund Epics whose prices are considered misleading or whose benefits are overstated. The social structure of PB and the distribution of resources across all members of the group also makes it harder for any single individual to negatively manipulate the final outcome.

- Follow SAFe guidance in establishing an experienced Epic Owner. While these individuals are expected to be advocates for their Epics, they should also be supported in developing realistic Lean Business Cases.

- Ensure that all Epics are presented in a common format. For example, instead of including NFRs for some Epics but not all Epics, ensure that all Epics either have NFRs or an explicit statement that a given Epic does not have NFRs.

- Use ranges for costs before the forum and then pick a cost within a range for a specific forum. Confirm the final cost with a member of the finance team.

- Conduct at least one calibration forum with leaders who can provide feedback on the cost estimates and description of the benefits. These calibration forums are powerful tools that enable organizations to leverage ‘the wisdom of the crowd’.

The most powerful approach listed above is to conduct calibration forums precisely because it is the most collaborative response to the potential misuse of manipulative cost estimates.

Dysfunction 1: Nothing truly big gets done

As the Solution Manager or Product Manager, I can ‘avoid’ the portfolio by only doing things that are smaller than the Epic threshold. The dysfunction is people trying to cheat the system by taking a large Epic and passing it off as a set of Features that go straight into Development Value Streams without appropriate review by the portfolio.

This is a very challenging dysfunction to identify and resolve because a significant part of the job of a Solution Manager or Product Manager is decomposing large requests into smaller Features that can be implemented by a Solution train or an ART.

This is a dysfunctional relationship between the value stream and the portfolio because it is designed to hide how money is being spent. More dangerously, this dysfunction often results in nothing ‘big’ getting done because large, multi-term investments need LPM support.

The following strategies can help eliminate this dysfunction.

- Ensure that the LPM investment guardrails are structured so that investments can – and at times, must be made – in larger Epics.

- Adjust the Epic threshold guardrail funding so that the balance between centralized and decentralized decision-making is promoted.

- Help Epic owners and business leaders responsible for baseline Solution investments realize that the purpose of the Epic threshold guardrail is to promote the best possible ideas. Certainly, not every idea should be framed as an Epic, and we want to promote decentralized decision-making. To balance this relationship, LPM teams should be comfortable with accepting ideas into the funnel and then rejecting these ideas not because they are bad ideas but because the LPM team is promoting the decentralization of the decision.

To illustrate, consider a Product Manager who wants to migrate from one Supplier for payment processing to a new Supplier. The PM might frame this as a Portfolio Epic and submit it into the Portfolio Kanban funnel. During the next Portfolio Sync, the portfolio team may decline to include the Epic because it is not considered a portfolio concern. The PM would then be given approval to pursue this Epic as a Solution Train or ART Epic outside of the LPM team but tracked across multiple PIs.

A sign that the relationship between Solution Managers, Product Managers, and the LPM team is the rate at which ‘big ideas’ are added to the LPM funnel. If an H2 or H1 Solution has zero new big ideas, the portfolio team should investigate the Solution Roadmap to identify potential Epics. If a Solution has submitted ‘ too many’ ideas into the Funnel, such as when an H1 solution is growing rapidly, it may suggest that the portfolio team may need to increase overall funding for the Solution.

Dysfunction 2: Choosing participants to bias the outcomes

In 2000, Mehrdad Baghai, Steve Coley, and David White from McKinsey & Company published The Alchemy of Growth, which introduced the perspective that portfolio management should have three time horizons. SAFe extends this framework to a fourth-time horizon to ensure that portfolios are allocating resources to decommission obsolete solutions.

The authors make the following observation about investment funding (p. 64):

The assumption that a company can search for opportunities without bias is false. When tradeoffs must be made between several economically attractive ideas, executive teams are deeply influenced by what they most want to do. For this reason, passion should be explicitly recognized in the search for opportunities. Putting a value on passion acknowledges that business creation is not a mechanistic process for planners but a human affair to which leaders bring their own emotions. It may mean assigning lower priority to some opportunities that show genuine promise, but in return, it gives the remaining ideas a better chance of success. Managers are more likely to devote their energy to ideas they believe in and care about.

The passion the authors recognize is one of the reasons why Participatory Budgeting is such a powerful tool: it provides each member of the LPM team with the forum they need to argue for their ideas in a manner that includes both economic and non-economic factors.

The downside to this passion is that the designers of the PB forums seek to unfairly influence the funding outcomes by choosing participants based on their a-priori preferences.

The best approach to eliminating this bias is to randomly select participants into PB forums based on roles and without regard to a-priori biases. A more restrictive rule is to explicitly disallow a forum participant from funding any Epic for which they are the Epic Owner. This ensures that if an Epic is funded, it is funded because it has support from at least one other person other than the Owner.

To determine the breadth of support, you can also introduce additional in-forum rules, such as requiring that every Epic must be funded by n people, where n>1. In some cultures, PB is engaged by a ‘Yes/No’ vote in which all of the funding is pooled, and the participants must all vote ‘Yes’ to fund an Epic from the common pool.

Dysfunction 3: Conflating reserving funds with spending funds

The cadence of LPM events does not always align with the spending requirements of the business. For example, a Supplier may have negotiated progress payments, including an up-front payment, which may not align with the funding.

Accordingly, Lean Portfolio Management works best if the leadership team distinguishes between reserving (or allocating) investment funds and spending (or releasing) investment funds. For example, the LPM team might reserve €14M for a development value stream that the finance team releases on a monthly basis as costs are incurred.

This enables a PB forum to focus on the higher-level purpose of the investments while leaving the details of cash flows to the finance team.

Myth 1: Leaders will only fund Epics that benefit them

During a consulting engagement, one of the authors supported a group consisting of numerous legal entities. Each entity operated autonomously with its own management and board of directors, presenting a common challenge to business leaders: How do we balance our individual needs with the needs of the collective? For SAFe practitioners using systems thinking, we can also frame this as: How can we optimize the system while recognizing that each part of the system is also an autonomous entity?

Heading into the PB session, the expectation, or rather the prevailing myth, was that each leader would solely finance their own Epics using their funds. This was further reinforced by perceived legal constraints for each entity that suggested that leaders could only fund Epics benefiting their entity.

However, as the German saying goes, “Wo ein Wille ist, da ist auch ein Weg” (“Where there is a will, there is a way”). In reality, participants had the ability to invest in different divisions or legal entities, as the final funding decisions ultimately fell under the purview of the respective company’s board of directors.

The law stipulates that leaders must prioritize the well-being of their own company, but it does not explicitly prohibit investments outside their immediate entity. In certain cases, such external investments are necessary for the overall prosperity of the legal entity – which is a convenient way of stating that leaders in the forums who “focused on the system” were able to make investments in any project that benefitted them directly or indirectly.

And indeed, this is what happened.

Participants in the forums cross-funded Epics, despite the perceived legal constraints. And even when there are no perceived legal constraints, we regularly see participants funding Epics that optimize the system.

Myth 2: Decision-makers will not listen to their extended leaders

One of the myths associated with PB is that it doesn’t make sense to invite an extended leadership team to participate in the forums because the LPM leadership team will simply ignore their feedback and make their own decision.

This myth is rooted in outdated models of command and control management practices and the challenges every enterprise faces in making choices about which decisions should be centralized and which can be decentralized. Because most LPM investment decisions are infrequent, long-lasting, and often associated with economies of scale, they meet the SAFe criteria for centralized decision-making, which recommends centralization of the allocation of funds and then decentralized control over how these funds are spent.

So why should a portfolio team engage their extended leadership team in PB forums?

The answer is simple: engaging extended teams in PB forums provides the LPM team with better information – and better information leads to better decisions. This is especially noticeable when the choices the extended leadership team makes run counter to those of the leaders: this is when leaders must take a step back and reconsider their choices.

bwin.party, a $1B+ revenue real-money gaming company, faced this situation when they compared the results of two forums with the executive teams (VPs and the C-Suite) to the result of four forums with the extended leadership team (Senior Directors and Directors).

Both executives and the extended leadership team in all six games funded the top two projects. A mix of senior leaders and executives funded the next five projects in five of six games.

However, some stark differences were noted. One Epic was a highly novel Epic that was not funded in either leadership forum but WAS funded in every extended leader forum. Upon further review, the leadership team changed their mind and funded the Epic.

Of course, we’re not saying that every single employee should be included in the PB program. Some employees will lack the technical expertise or business training required to provide meaningful input into portfolio decisions. We are saying that PB creates better data for high-impact decision-making when extended leadership teams are included.

Consequences during implementation when using Color of Money

In this section, we explore two consequences that arise during implementation when using Color of Money.

The first consequence concerns the design of value streams and ARTs.

The Color of Money concept provides a method to ensure that funds designated for specific Epic align with the funding constraints associated with the source of the funds. For example, green money is allocated for green Epics, blue money for blue Epics, and so forth.

However, the process of funding, communicating, and managing these funds goes beyond mere categorization. When operating under strict regulations, it becomes imperative to guarantee that the funds allocated for a particular color are exclusively utilized for Epics falling within that specific category. This necessitates the establishment of traceability mechanisms to ensure the proper allocation of funds.

To achieve this, traceability measures must be put in place, allowing for a transparent record of how the money of each color is utilized. This ensures that funds are directed towards Epics aligned with their designated color, maintaining the integrity of the funding decision.

This can be implemented in SAFe by organizing ARTs around solutions that align with the funding requirements. We acknowledge that may cause some challenges in organizing around value or when Epics impact multiple solutions. However, in this case, the funding constraints may override other considerations in the design of the value streams.

The second consequence concerns how excess or unused funds are managed.

In the absence of the color of money, unused funds, such as when an Epic hypothesis is proven or disproven more cheaply than forecasted, are simply returned to the portfolio for re-allocation. This ensures that resources are efficiently managed and prevents excess funds from being left idle or misallocated.

When these funds are associated with the Color of Money, they must be returned in a way that preserves their original restrictions.

Conclusion

We know Participatory Budgeting (PB) is a valuable tool in Lean Portfolio Management (LPM) for allocating the portfolio budget to funding Epics and value streams. However, the assumption that PB is free of constraints in fund allocation limits its application in various portfolio scenarios. Regulatory constraints, such as earmarked funds and spending regulations, as well as policy constraints, such as investment allocation and capacity allocation guardrails, influence the allocation of portfolio budgets.

To address these constraints, PB forums can be designed to accommodate them, expanding the use of PB within enterprises. By understanding and identifying the color of money constraints and Epic constraints, LPM practitioners can navigate the limitations and make informed decisions. The design of PB forums can enforce constraints through hard rules, manage constraints with soft rules, or even ignore constraints for market research purposes.

By incorporating constraints and effectively managing them in PB forums, enterprises can enhance alignment, portfolio flow, and funding for epics. The integration of constraints into the PB process promotes better decision-making and ensures compliance with regulatory and policy requirements. Overall, embracing the design considerations and strategies outlined in this article can maximize the benefits of PB in Lean Portfolio Management.

In conclusion, the concept of the ‘color of money’ serves as a crucial mechanism for ensuring the appropriate and timely use of funds for specific purposes. It involves the establishment of constraints, guardrails, or hard rules to govern the allocation and utilization of money. Implementing traceability mechanisms and processes to return surplus funds to the portfolio is essential in ensuring that allocated funds are effectively utilized and aligned with designated Epic. This approach is vital for adhering to legal requirements and preventing any violations of laws or regulations. By embracing these practices, organizations can ensure law-compliant use of funds within their operations.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Brian Tucker, Simon Chesney, Adam Mattis, Thorsten Janning, Steve Mayner, Harry Koehnemann, Rebecca Davis, and Dean Leffingwell for their review and feedback.

References

Framework Articles:

- Participatory Budgeting: https://scaledagileframework.com/participatory-budgeting/

- Portfolio Kanban: https://scaledagileframework.com/portfolio-backlog/

- Adopting Lean Budgeting Aligned to Development Value Streams: https://scaledagileframework.com/government-adopting-lean-budgeting-aligned-to-value-streams/

Additional references:

[1] Hohmann, Luke. How to Prioritize Your Project Portfolio Using Conteneo Collaboration Games: A Playbook in the Epic Wins Series. https://www.amazon.com/Prioritize-Project-Portfolio-Conteneo-Collaboration-ebook/dp/B00I0IE5OG/. 2014 [2] UN-Habitat. 72 Frequently Asked Questions about Participatory Budgeting. https://unhabitat.org/72-frequently-asked-questions-about-participatory-budgeting. 2004. [3] UN-Habitat. Exploring the Role of Participatory Budgeting in Accelerating the SDGs: A Multidimensional Approach in Escobedo, Mexico. https://unhabitat.org/exploring-the-role-of-participatory-budgeting-in-accelerating-the-sdgs-a-multidimensional-approach. 2020.Last Update: 11 September 23